Cries and Whispers, 1972, Ingmar Bergman

By 1972, Bergman was already established as one of the titans of international art cinema. He had won several awards at Cannes and been nominated for two Academy Awards (he would eventually be nominated for 9, including three for this film). Cries and Whispers is not a film that could be made by anyone. It could not have been made by Ingmar in his younger years. It could be seen as a spiritual sequel to Persona, which was really his first foray intro surrealism and immersive, abstract character exploration. Cries and Whispers does not share many thematic or plot elements with this predecessor, but it does utilize the supernatural and it explores these four characters nearly as deeply as the two (or one?) in Persona.

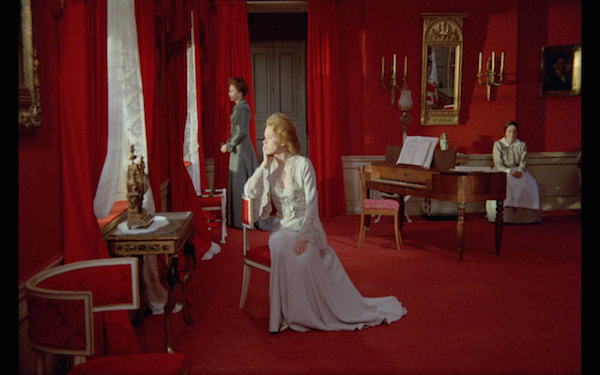

Another similarity between this and Persona is the visual canvas. Persona was in black and white, but I think of it as starkly black and starkly white, almost to the point where it has the same effect as a color film. Cries and Whispers is a color film, but it is nearly a red and white film. The reds are stark and stunning, while the whites are a contrast, just like the whites were in Persona. The colors are visual motifs as well, as red signifies death, mutilation, and white represents the innocence of a lost and nearly forgotten childhood. Sven Nykvist rightfully won an Oscar for his work, and Bergman and crew deserve praise for creating such a visually remarkable red-and-white world.

The color of red is used most effectively for the scene transitions. At the end of a scene, the image dissolves into a red canvas, which gives it a surreal quality. It is a continual reminder of the central theme of death, as Agnes fights her battle with uterine cancer. Sometimes Bergman freezes in the middle of the dissolve, holding on the blood red screen to give us time to ponder and process the meaning of the scene. These transitions and the slight deviations with each one heightens the impact of the color red. I can think of many movies that have used a single color to dictate the theme, some of which are done well (Kieslowski’s Red for example), but none that used it to this extreme, creating what is basically a red and white film.

Please be warned that from here on our I will be delving into spoiler territory.

Harriet Andersson as Agnes gives the most memorable and challenging performance as she tries to cope with the pain and her imminent, unavoidable death. The anguish on her face is heartbreaking and convincing. Much of her performance is given in grunts and grimaces. She is at her most vocal at the very end of the film, but this is after she has passed and the pain has left her. Only the loneliness and the yearning for comfort remains. She seeks solace from her two sisters, yet receives it only from her housemaid Anna (Kari Sylwan) in an unusual yet effective manner.

The sisters, Maria (Liv Ullmann) and Karin (Ingrid Thulin) are complicated characters, at times polar opposite from each other, yet there is some grey (or red?) area in between. To her sisters, Karin is stoic and stubborn, refusing and being repulsed by intimate contact. Maria is affectionate and compassionate, yet she is unscrupulous, making out with the doctor watching over Agnes. In flashback we see Maria and the doctor having an affair, which results in her husband attempting suicide. Karin also flashes back, but her memory is of fidelity and mutilation. She says “nothing but a web of lies” as she abuses herself with broken glass and then exhibits a grisly scene for her stunned husband.

At Agnes’ funeral, the priest says that they had many talks and her faith was stronger than his. Is this why she is able to come back? This is never explained, but the ensuing revisitation with Anna and the sisters has differing results. Maria, who was affectionate to Agnes in life, rejects her in death. Karin also rejects and hates her resurrected sister. Again, the only character that gives her any comfort is Anna, yet the living relatives treat her with scorn and dismiss her as if she was a piece of trash.

The film can be interpreted a number of ways. It speaks to the intimacy (or lack thereof) of family, and how familial love and companionship is fleeting and unobtainable in later life and especially in death. It speaks to the wickedness of the upper class, and how true camaraderie and goodness comes from those that are not clouded by a privileged upbringing. It also says that personal relationships are ultimately rooted in selfishness. With their husbands and other sisters, the sisters care only for what they receive. The same is true about Agnes, who we learn little about, but she is also selfish for intimacy and companionship. The only true altruistic and benevolent character is Anna. She pledges to care for Agnes in life and in death with no financial recompense. At least Maria, who despite her flaws is the most considerate of the other primary characters, and gives Anna a little something to help. Maybe there is hope for humanity yet.

Film Rating: 8/10

Supplements

Bergman Introduction: 2003 on the Island of Fårö.

This project came about in winter on the island. It was melanchology time for him because he had just been broken up with someone. He was lonely with only a Dachshund to keep him company. He had an image of a room completely in red. He believes that if the image persists, you should keep writing.

Harriet Andersson – 2012 Stockholm interview with Peter Cowie.

This was just like the interview on the Summer with Monika disc, and was probably recorded in the same session. Harriet was again very animated and descriptive. She is a great interview at an older age.

It had been 10 years since she had worked with Ingmar. At first she rejected the part because it was too difficult. He said, “Don’t give me that load of crap,” and she took it.

The castle set was wonderful. They had offices downstairs. The red rooms were the studio on the main floor. The floor above was for make-up and wardrobe. Ingmar had said the red room resembled the inside of the womb. Andresson: “Well he says things.” “He like to make small stories.” She implies that he is telling a tale.

They kept her awake at night and that made her look tired. The death scenes were an imitation of her father, which she witnessed. He had a terrible death. She has trouble watching the film now because of that memory.

On-set Footage Silent color footage with audio commentary from Peter Cowie.

This is the highlight of the disc. They have quite a bit of silent behind the scenes footage that includes the set-up, press conference, actresses on location in and out of the house, the cast and crew being fed, editing of the film, rehearsals, and so forth. It is a wealth of material and Cowie gives numerous factoids on the film just by talking over the images. This was almost as satisfying as a good audio commentary.

They talk a great deal about the playwright Strindberg. He had spent summers at the manor that they used as a boy and took inspiration of Miss Julie from lady of the manor. Bergman had adapted Strindberg plays for stage, but never for film. One interesting point is that Bergman’s films were not very popular in his home country, but his Strinberg plays were exceptionally popular.

Ingmar Bergman Reflections on Life, Death and Love: 1999 television interview with Erland Josephson.

This is another enjoyable interview. They do not talk about the films so much as they do personal lives, loves, relationships, and various other topics. Bergman is surprisingly candid.

They talk about children. They both have quite a few (Bergman has nine). Bergman talks about apologizing to one of his children for being a terrible father, when the son says that he hasn’t been a father at all. They all get together every year at Fårö Island and the children have maintained good relationships. None of his children were planned. “They were all love children.”

The women lasted about 5 years until he found a new one, and then he found Ingrid, and then she died. When she decided to marry him, “all other traffic ceased.” He was truly in love. He is friendly with all the other girls that he was ever with, and many (including Liv and Harriet) became part of his acting stable. Elrand points out that all the bitterness subsides over time. With Ingrid he had a close relationship, and he has reverted to solitude now that she’s gone.

They talk about death and the inevitability, and how Ingmar doesn’t fear it so much but Elrand does. Of course he talks about Ingrid and how he planned to leave Fårö to her, but her passing happened and it crushed him. You can tell that his life was still devastated by it even all those years later.

On Solace: Video Essay from :kogodana:.

This is an interesting essay, unlike most on Criterion discs. It uses images and text well, especially the red title cards with white text.

The concept of the three movements is abstract to a degree, and it is easier to watch than for me to explain it here. Basically he says that there are three movements. The first two movements are flashbacks, while the third is a distillation.

He points out a few insightful observations, such as that Karin’s mutilation is inverse of Agnes’ uterine cancer. The final scene recalls “bodily solace” that Anna gives Agnes in earlier scene, which is the central theme of the movie and the thesis of his essay.

Criterion Rating: 9/10

Posted on July 3, 2015, in Criterions, Film and tagged criterion, death, film, harriet andersson, ingmar bergman, Ingrid Thulin, Kari Sylwan, liv ullmann, peter cowie, Sven Nykvist, the criterion collection. Bookmark the permalink. 3 Comments.

Excellent review.

Thanks! This was a tough one. It’s never easy to write about Bergman.

Fantastic post! I really need to explore more of his work.