On the Waterfront: The Great Performances

“When you weighed one hundred and sixty-eight pounds you were beautiful.” – Charley Malloy.

“It was you, Charley.” – Terry Mallow.

We’ll get to Terry (Marlon Brando) and Charley (Rod Steiger) soon enough, especially the famous scene from the image above. Even though that sequence is iconic and has one of the most memorable lines ever delivered in film, there is far more to the acting in On the Waterfront than any particular scene.

Kazan has often been described as an “Actor’s Director.” There’s more truth to that statement than many might realize. He began his directorial career in theater, but rather than stick to the traditional acting styles, he searched for something new and vibrant. He wanted something realistic that people could identify with. He drew from the Stanislavski System, worked with Lee Strasberg, and founded the Actor’s Studio in 1947. Many of the actors from this studio would become regulars in Kazan films, and many would subsequently become Hollywood Stars. The most notable, Marlon Brando, is considered by many to be the best actor that ever lived.

By 1954, Kazan had successfully implemented his acting system to the big screen. His greatest success was in adapting Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire, which won three out of the four acting categories (Brando lost). That and other of his films were revolutionary when it came to the acting, but even Streetcar had a theatricality about it. Even though the acting was superb, it did not have the intense realism that was being imported from overseas, specifically Italy. On the Waterfront would change that, and Kazan considers it the one film where the final product was closest to his original vision.

In addition to Brando and Steiger, who were established method actors, there were other Actor’s Studio alums, including Lee J. Cobb, Eva Marie Saint, and Karl Malden. These performances all stand out, and all were nominated for Academy Awards, with Brando and Saint winning. The strength of the acting extends all the way down to amateurs and extras. Just about every human being in the film is convincingly real, whether they deliver one line of dialogue or several.

Johnny Friendly, portrayed by Lee J. Cobb

Cobb had worked with Kazan as Willy Loman on stage in Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman. He was no stranger to the method and could play a variety of characters. He would have quite a career. He is often overlooked for his work as Johnny Friendly, but that is mostly based on the strength of his co-stars. He is the ideal villain. While he does not show the same humanity that Terry and Charley show, we understand that his fiery, combative motivation comes from a sense of self preservation.

Johnny probably did not always come off as the villain. We get a sense in the early scenes that he was a mentor for the Malloys when they were kids. That may have been based on his own self-interest of indoctrinating them into the system, casting favor onto them so they would remain loyal and not “squeal,” but all the same, the hostility Terry would feel toward him was likely a new development. Johnny would remind them where they came from, but he also expected them to do his bidding without question. If someone crosses him, they were gone. It could be something as small as getting a money count wrong (which implies stealing) or worse, talking about their operation to the commission.

Cobb’s performance is nuanced to a degree, in that we see him calmly giving out orders, maintaining his composure under some pressure, while we also see him in a state of fury and rage when the situation calls for it. The ending confrontation between Johnny and Terry is legendary, with an amazing, explosive exchange between both actors.

Father Barry, portrayed by Karl Malden

Terry Malloy might be the protagonist of the film, but Father Barry is unquestionably the “good guy.” He is a local Catholic priest who exhibits real concern and passion for the people who are being taken advantage of down at the docks. Rather than play the priest in stereotypical, solemn fashion, he strikes a balance between Barry’s obsession toward righting the wrong, and even his toughness by standing up to the organized local that he knows has been guilty of terrible crimes including murder.

When he is talking to the dockworkers, especially Terry Mallow, he is understanding of their fears and concerns, while also taking upon himself to get them to take action. He uses religion when needed to prove his point that acting against those in power is not only in the people’s interest, but is in God’s interest as well. When Terry Malloy tells him, “If I spill, my life ain’t worth a nickel,” he quickly retorts, “How much is your soul worth if you don’t?” Most importantly, he is not afraid for his own well being, and in this respect he is one-sided, but Malden adds as much dimension and tenacity as he can.

Edie Doyle, portrayed by Eva Marie Saint

Brando tends to get credit for the great performance in the film, but his work was enhanced by the great work of the people he acted with. Saint was a newcomer to acting, but she had also been educated via the Actor’s Studio. She was also personally similar to her character. She was a scared, inhibited, naive 19-year-old.

Edie is a fragile character, still dealing with the loss of her brother, while being pursued aggressively by Terry. She is reluctant to open up, partly due to her sensitivity with the loss fresh in her mind, but also because of her reservations with Terry’s favored position by the locals in power. She becomes embroiled in the quest of Father Barry and the confidence of Terry Malloy, who is torn as to what he should do. Through her performance, we understand Saint’s manic reaction to what is going on around her. During the wedding scene, she is literally crying at one point, and tentatively dancing with Malloy moments later. Her performance is magnificent, and she helps endear us to both characters, making them more sympathetic.

Charley Malloy, portrayed by Rod Steiger

Rod Steiger has been accused often of over-acting and being hammy. I touched on that to an extent when reflecting on Jubal. He does the same thing on occasion in On the Waterfront. He plays Terry’s brother Charley, who is a ranking member of the union mob.

Most of the time Steiger stays in the character of the henchman and trusted man of Johnny Friendly, fighting his battles, even if those are against his own brother. At times he is quietly obedient to his boss, while at others he would raise his voice and thunderously bash someone who either does not conform to the system or rejects it. He is a company man, through and through. Steiger is excellent in the role, one of the few times I think he has shown his true potential as an actor (the other is The Pawnbroker, which should have landed Steiger an Oscar).

While Steiger has many bright moments, he was at his best during the cab scene. I’ll come back to that momentarily.

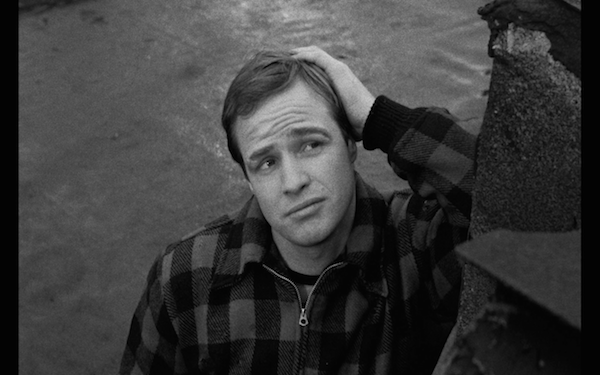

Terry Malloy, portrayed by Marlon Brando

I consider Marlon Brando’s performance in On the Waterfront to be the greatest of all time. Some have dismissed him of basically playing a mumbling, gum-chewing buffoon, but that’s part of the strength of the performance. He is a buffoon, but so is Terry Malloy, a former prizefighter with barely any education. Brando is completely realistic in the role, using the vernacular of the waterfront and fitting in with the locals, many of whom were extras that actually were Longshoremen.

Brando is not only engaging and entertaining to watch, but he also carries the personal nuance and sensitivity that his character needs. We need to believe that he would be respected by the mob, yet also they could be afraid of him and what he knows. We need to believe that he is charming enough to lure Edie to his side, while also sensitive enough to not scare her away. We need to believe that this is a man who used to knock people out for a living, who now works at the docks, yet spends his spare time caring for pigeons on a rooftop. The audience has to like the character as much as Edie and Father Barry do, and we have to rally behind him in order to make the plot and ending work. He has to become the underdog.

Brando puts on a clinic with method acting. Yes, he does chew gum. He fidgets and plays with his hair, but these are all things that normal people do. That’s what Kazan was going for. He did not want someone like Ralph Richardson or Laurence Olivier (both fantastic actors, just different). He wanted someone who could act naturalistic at and around the docks. Using props, gestures and body mannerisms was one of the ways Brando would keep himself on his toes. He needed to be distracted enough in the scene that he could be convincing at being the person, and not just enunciating some previously written lines. His performance has the feeling of an improvisation, and some of the best moments come from material that he and his co-stars previously improvised.

The courting scene between Terry and Edie is a classic, and is notable for the use of the glove. She drops her glove while he is trying to talk to her. He picks it up, plays with it, and eventually puts the glove on, hinting at some sexuality. By this action, with her personal belonging invaded, she gets a little more comfortable and closer to him. They are connected with that glove. When she takes it back at the end of the scene and puts it back on her hand, she is a changed woman and the relationship has made progress.

The glove scene came out of an improvisation during rehearsal. She dropped the glove and Kazan let them keep going. Many directors would have stifled this creativity, but the actors made it work and Kazan used it in the completed film. It is one of the most memorable scenes in the film.

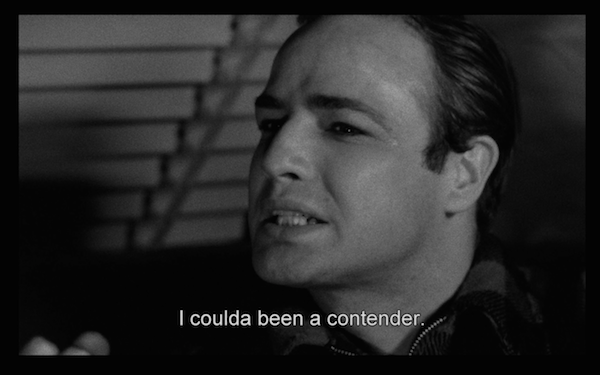

The Contender

If you haven’t seen On the Waterfront, you’ve probably heard of or seen the infamous cab scene and the “Contender” line somewhere before. I’ve seen the movie about 3-4 times, but I’ve seen the cab scene easily a dozen times, maybe two dozen, and it gets to me every time. Even though it stands alone as an exceptional scene, it is the culmination of the performances up to that point that really makes it special.

We learn through dialogue and exposition that Terry used to be a boxer, but that his career ended because he had to take a dive. We do not learn the caliber a fighter he was, or the perspective of Charley until the cab scene.

The scene begins with Charley trying to talk some sense into his brother. He doesn’t want him to testify at the commission. When he makes little progress, he uses violent manipulation, probably the same way he has used it many times before. He pulls a gun on his brother and demands that he take a comfortable job in exchange for his silence. This is where Steiger’s propensity for big acting really works. When Terry refuses and Charley realizes that he might testify, things get heated. The performance reaches an unexpected point of tension when the gun comes out. The way Brando reacts is touching. Rather than cowering in fear or getting defensive, he just shakes his head, says his brothers name, and slowly pushes the gun away. He is not angry, just disappointed.

From there, the situation completely changes and the brothers are on even footing. There’s no way that Charley could kill his brother, and him pulling the gun was as empty a threat as he could muster. The scene picks up in this YouTube and this is where the magic really begins.

Even though the “Contender” line is the famous one (#3 on AFI’s Greatest Quotes list), there are another four words that really cut to the heart of the matter and are the most affecting. “It was you, Charley.” They reminisce about old times. He talks of Terry when he was 168 pounds and beautiful, how he could have been “another Billy Conn.” Charley blames it on a manager. No, “it wasn’t him Charley, it was you,” Terry says.

From there the speech happens.

I coulda had class. I coulda been a contender. I could’ve been somebody, instead of a bum, which is what I am. Let’s face it. It was you, Charley.

Brando delivers the speech with gusto, with passion, with precision. Terry has been waiting ever since that fateful night where he took the dive and lost his shot, feeling resentful towards his brother the whole time. He does not overact here. He does not scream with rage. His words are those of disappointment, of dejection. His dreams were shattered, and finally he can express himself to the man who crushed them, all to make a quick buck.

The rush of passion is gone when he says “It was you, Charley.” The line is delivered with just a feeling of shame for his brother, that he was so short-sided that he ended a dream.

Steiger does not get the credit he deserves for this scene, but the way he reacts is just as important to the scene as the way Brando delivers the dialogue. The way Steiger is silent and expressionless as the words hit him enhances the scene. He is clearly affected by the remarks his brother has made, and immediately changes direction, which seals his fate. He loves his brother and realizes that it was him. There is no overacting here, just acceptance. “Okay, okay,” he says. That’s it.

Through these few minutes, we have someone pulling a gun on his brother, and then just moments later, giving the gun up and sacrificing himself out of love. We see a brief glimpse of Charley, the authoritarian figure, when he barks at the driver, “You, you pull over.” The rest plays out as it has to.

Having seen the scene so many times, it is difficult to put into words how meaningful and memorable it is. The only way I can describe it is beautifully tragic. It is pure power. Brando and Steiger, through Kazan and a makeshift set, made one of the highest points of American cinema in a matter of minutes. It is still remembered vividly 60 years later, and will continue to be remembered as a key part of cinema history.

Posted on May 15, 2015, in Essays, Film. Bookmark the permalink. 12 Comments.

Good stuff! The film has gone through an underappreciated phase, I think, which maybe the Criterion release has helped to rectify. By the way, Brando, Saint, Cobb, Malden and Steiger were all Oscar-nominated, with the first two winning.

Thanks! It is definitely under-appreciated today. The Criterion was released in 2013, but still probably helped put it back on the map. Thanks for the Oscar correction. I was looking at the wins instead of the nominations. Cobb, Malden and Steiger probably canceled each other out because O’Brien won for Barefoot Contessa. All three were more deserving in my opinion, but I would have given Steiger the statue.

It’s true that Cobb’s performance isn’t as noted today just because the others’ performances are so marvelous, but it is so believable (and chilling as a result). I liked your focus on each of the performances here, which reminds me of my initial viewing, and what a shock it was to see a film of this caliber for the first time.

Cobb really plays the quintessential villain, scary because the characters both rely on and fear him. He was quite the actor and I love him in other films (12 Angry Men for starters!).

Sometimes I think we start to take the greatness in “On the Waterfront” for granted, and that is a huge mistake. One that you are putting right.

Thanks, Patricia. Just doing my part. 🙂

I know that even though I loved the film, I took it for granted before this revisitation.

You’ve found your niche, Aaron. The composition of this piece is brilliant. It’s like you cycled to the top of a steep climb and are flying down the other side. Well done!

Thanks, Jim. I felt really good about this piece, but with such great material, it practically wrote itself.

My dear, you were SO RIGHT about writing an article on the actor performances’ in this film, because they were all incredible. A thoughtful article, pleasant to read.

Thank you, Virginie! If there was a movie to write a single article about just the performances, this was it.

Pingback: My Favorite Classic Movie Blogathon: On the Waterfront | Criterion Blues .....

Pingback: On the Waterfront, 1954, Elia Kazan | Criterion Blues .....